|

|

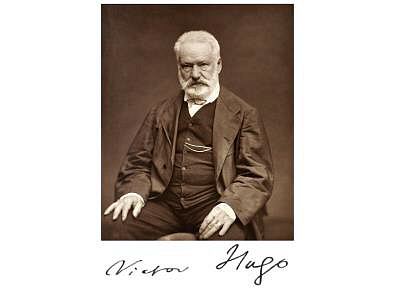

(Les Travailleurs de la Mer) by Victor Hugo The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (Paris, 1831) Victor Marie Hugo was born on 26th February 1802 at the ancient city of Besançon in Eastern France. His political views were firm and radical, though somewhat variable. Hugo was elevated to the peerage by King Louis-Philippe, but his opposition to Louis Napoleon's seizing power in 1851 led to his exile in Jersey, from where he was, in turn, expelled for criticising Queen Victoria. He finally settled in Guernsey, returning to France in 1870 as a significant national hero. Abridged: JH/GH For more books by Victor Hugo, see The Index I. - A Lonely Man A Guernseyman named Gilliatt, who was avoided by his neighbours on account of lonely habits, and a certain love of nature which the suspicious people regarded as indicating some connection with the devil, was one day returning on a rising tide from his fishing, when he fancied he saw in a certain projection of the cliff a shadow of a man. The place probably attracted Gilliatt's gaze because it was a favourite sojourn of his - a natural seat cut in the great cliffs, and affording a magnificent view of the sea. It was a place to which some uninitiated traveller would climb with delight from the shore and sit entranced by the scene before him, all oblivious of the rising ocean till he was completely cut off from escape. No shout would reach the ear of man from that desolate giant's chair in the rock. Gilliatt steered his ship nearer to the cliff, and saw that the shadow was a man. The sea was already high. The rock was encircled. Gilliatt drew nearer. The man was asleep. He was attired in black, and looked like a priest. Gilliatt had never seen him before. The fisherman wore off, skirted the rock wall, and, approaching so close to the dangerous cliff that by standing on the gunwale of his sloop he could touch the foot of the sleeper, succeeded in arousing him. The man roused, and muttered, "I was looking about." Gilliatt bade him jump into the boat. When he had landed this young priest, who had a somewhat feminine cast of features, a clear eye, and a grave manner, Gilliatt perceived that he was holding out a sovereign in a very white hand. Gilliatt moved the hand gently away. There was a pause. Then the young man bowed, and left him. Gilliatt had forgotten all about this stranger, when a voice hailed him. It was one of the inhabitants, driving by quickly. "There is news, Gilliatt - at the Bravées." "What is it?" "I am too hurried to tell you the story. Go up to the house, and you will learn." The Bravées was the residence of a man named Lethierry. He had raised himself to a position of wealth by starting the first steamboat between Guernsey and the coast of Normandy; he called this vessel La Durande; the natives, who prophesied evil of such a frightful invention, called it the Devil's Boat. But the Durande went to and fro without disaster, and Lethierry's gold increased. There was nothing in all the universe he loved so much as this marvellous ship worked by steam. Next to the Durande, he most loved his pretty niece Dérouchette, who kept house for him. One day as Gilliatt was walking over the snow-covered roads, Dérouchette, who was ahead of him, had stopped for a moment, and stooping down, had written something with her finger in the snow. When the fisherman reached the place, he found that the mischievous little creature had written his name there. Ever since that hour, in the almost unbroken solitude of his life, Gilliatt had thought about Dérouchette. Now that he heard of news at the Bravées, the lonely man made his way to Lethierry's house, which was the nest of Dérouchette. The news was soon told. The Durande was lost! Presently, amid the details of the story - the Durande had been wrecked in a fog on the terrible rocks known as the Douvres - one thing emerged: the engines were intact. To rescue the Durande was impossible; but the machinery might still be saved. These engines were unique. To construct others like them, money was wanting; but to find the artificer would have been still more difficult. The constructor was dead. The machinery had cost two thousand pounds. As long as these engines existed, it might almost be said that there was no shipwreck. The loss of the engines alone was irreparable. Now, if ever a dream had appeared wild and impracticable, it was that of saving the engines then embedded between the Douvres. The idea of sending a crew to work upon those rocks was absurd. It was the season of heavy seas. Besides, on the narrow ledge of the highest part of the rock there was scarcely room for one person. To save the engines, therefore, it would be necessary for a man to go to the Douvres, to be alone in that sea, alone at five leagues from the coast, alone in that region of terrors, for entire weeks, in the presence of dangers foreseen and unforeseen - without supplies in the face of hunger and nakedness, without companionship save that of death. A pilot present in the room delivered judgment. "No; it is all over. The man does not exist who could go there and rescue the machinery of the Durande." "If I don't go," said the engineer of the lost ship, who loved those engines, "it is because nobody could do it" "If he existed - - " continued the pilot. Dérouchette turned her head impulsively, and interrupted. "I would marry him," she said innocently. There was a pause. A man made his way out of the crowd, and standing before her, pale and anxious, said, "You would marry him, Miss Dérouchette?" It was Gilliatt. All eyes were turned towards him. Lethierry had just before stood upright and gazed about him. His eyes glittered with a strange light. He took off his sailor's cap, and threw it on the ground; then looked solemnly before him, and without seeing any of the persons present, said Dérouchette should be his. "I pledge myself to it in God's name!" II. - The Prey of the Rocks The two perpendicular forms called the Douvres held fast between them, like an architrave between two pillars, the wreck of the Durande. The spectacle thus presented was a vast portal in the midst of the sea. It might have been a titanic cromlech planted there in mid-ocean by hands accustomed to proportion their labours to the great deep. Its wild outline stood well defined against the clear sky when Gilliatt approached in his sloop. The rocks, thus holding fast and exhibiting their prey, were terrible to behold. There was a menace in the attitude of the rocks. They seemed to be biding their time. Nothing could be more suggestive of haughtiness and arrogance: the conquered vessel, the triumphant abyss. The two rocks, still streaming with the tempest of the day before, were like two wrestlers sweating from a recent struggle. Up to a certain height they were completely bearded with seaweed; above this their steep haunches glittered at points like polished armour. They seemed ready to begin the strife again. The imagination might have pictured them as two monstrous arms, reaching upwards from the gulf, and exhibiting to the tempest the lifeless body of the ship. If Gilliatt had known how she came to be there, he might have been more awed by the tremendous spectacle. The cause was an accident, and yet a purposed act. Clubin, the captain, as smug a hypocrite as ever scuttled a ship, had intended to run the Durande on the Hanways. His belt contained three thousand pounds. He meant to lose the ship on the Hanways, a mile from shore, and when the passengers had rowed away, pretending that he would go down with the ship, Clubin purposed to swim to land, get on board a pirate ship, and be off to the East. His little drama had been acted out; the boats had rowed away, everybody praising Captain Clubin, who would not abandon his ship. But when the fog cleared - horror of horrors! - Clubin found himself not on the Hanways, but on the Douvres; not one mile from shore, but five miles! Clubin saw a ship in the distance. He determined to swim to a rock from which he could be seen, and make signals of distress. He undressed, leaving his clothing on deck. He retained nothing but his leather belt, and then, precipitating himself head first, plunged into the sea. As he dived from a height, he plunged heavily. He sank deep in the water, touched the bottom, skirted for a moment the submarine rocks, then struck out to regain the surface. At that moment he felt himself seized by one foot. But of all this Gilliatt, arriving at the Douvres, knew nothing. He was absorbed by the spectacle of the ship held in mid-air. And what did he find? The machinery was saved, but it was lost. The ocean saved it, only to demolish it at leisure - like a cat playing with her prey. Its fate was to suffer there, and to be dismembered day by day. It was to be the plaything of the savage amusements of the sea. For what could be done? That this vast block of mechanism and gear, at once massive and delicate, condemned to fixity by its weight, delivered up in that solitude to the destructive elements, could, under the frown of that implacable spot, escape from slow destruction seemed a madness even to imagine. Gilliatt looked about him. When he had made a lodging for himself, and had suffered the misfortune of losing the basket containing his provisions, Gilliatt considered his difficulties. In order to raise the engine of the Durande from the wreck in which it was three-fourths buried, with any chance of success - in order to accomplish a salvage in such a place and such a season, it seemed almost necessary to be a legion of men. Gilliatt was alone. A complete apparatus of carpenter's and engineer's tools and implements were wanted. Gilliatt had a saw, a hatchet, a chisel, and a hammer. He wanted both a good workshop and a good shed; Gilliatt had not a roof to cover him. Provisions, too, were necessary on that bare rock, but he had not even bread. Anyone who could have seen Gilliatt working on the rock during all that first week might have been puzzled to determine the nature of his operations. He seemed to be no longer thinking of the Durande or the two Douvres. He was busy only among the breakers. He seemed absorbed in saving the smaller parts of the shipwreck. He took advantage of every high tide to strip the reefs of everything that the ship-wreck had distributed among them. He went from rock to rock, picking up whatever the sea had scattered - tatters of sail-cloth, pieces of iron, splinters of panels, shattered planking, broken yards; here a beam, there a chain, there a pulley. He lived upon limpets, hermit-crabs, and rain-water. He was surrounded by a screaming garrison of gulls, cormorants, and sea-mews. The deep boom of the waves among the caves and reefs was never out of his ears. By day he was roasted in the terrific heat which beat with pitiless force on this exposed pinnacle; at night he was chilled to the marrow by the cold of the open sea. And for ever he was hungry, thirsty - famished. One day, in exploring for salvage some of the grottoes of his rock, Gilliatt came upon a cave within a cave, so beautiful with sea-flowers that it seemed the retreat of a sea-goddess. The shells were like jewels; the water held eternal moonlight. Some of the flowers were like sapphires. Standing in this dripping grotto, with his feet on the edge of a probably bottomless pool, Gilliatt suddenly became aware in the transparence of that water of the approach of some mystic form. A species of long, ragged band was moving amid the oscillation of the waves. It did not float, but darted about at its own will. It had an object; was advancing somewhere rapidly. The thing had something of the form of a jester's bauble with points, which hung flabby and undulating. It seemed covered with a dust incapable of being washed away by the water. It was more than horrible; it was foul. It seemed to be seeking the darker portion of the cavern, where at last it vanished. Gilliatt returned to his work. He had a notion. Since the time of the carpenter-mason of Salbris, who, in the sixteenth century, without other helper than a child, his son, with ill-fashioned tools, in the chamber of the great clock at La Charité-sur-Loire, resolved at one stroke five or six problems in statics and dynamics inextricably intervolved - since the time of that grand and marvellous achievement of the poor workman, who found means, without breaking a single piece of wire, without throwing one of the teeth of the wheels out of gear, to lower in one piece, by a marvellous simplification, from the second story of the clock tower to the first, that massive clock, large as a room, nothing that could be compared with the project which Gilliatt was meditating had ever been attempted. After incredible exertions, the machinery was ready for lowering into the sloop. Gilliatt had constructed tackle, a regulating gear, and made all sure. The long labour was finished; the first act had been the simplest of all. He could put to sea. To-morrow he would be in Guernsey. But no. He had waited for the tide to lift the sloop as near to the suspended engines as possible, and now the funnel, which he had lowered with the paddle-boxes, prevented the sloop from getting out of the little gorge. It was necessary to wait for the tide to fall. Gilliatt drew his sheepskin about him, pulled his cap over his eyes, and lying down beside the engine, was soon asleep. When he woke, it was to feel the coming of a storm. A fresh task was forced upon this famished man. It was necessary to build a breakwater in the gorge. He flew to this task. Nails driven into the cracks of the rocks, beams lashed together with cordage, cat-heads from the Durande, binding strakes, pulley-sheaves, chains - with these materials the haggard dweller of the rock built his barrier against the wrath of God. Then the storm came. III. - The Devil-Fish When the awful rage of the storm had passed, and the barrier which he had repaired in the midst of the tempest hung like a broken arm across the gorge, Gilliatt, maddened by hunger, took advantage of the receding tide to go in search of crayfish. Half naked, and with his open knife between his teeth, he sprang from rock to rock. In hunting a crab he found himself once more in the mysterious grotto that glittered with jewel-like flowers. He noticed a fissure above the level of the water. The crab was probably there. He thrust in his hand as far as he was able, and groped about in that dusky aperture. Suddenly he felt himself seized by the arm. A strange, indescribable horror thrilled through him. Some living thing - thin, rough, flat, cold, slimy - had twisted itself round his naked arm. It crept upward towards his chest. Its pressure was like a tightening cord, its steady persistence like that of a screw. In less than a moment some mysterious spiral form had passed round his wrist and elbow, and had reached his shoulder. A sharp point penetrated beneath the arm-pit. Gilliatt recoiled; but he had scarcely power to move. He was, as it were, nailed to the place. With his left hand, which was disengaged, he seized his knife, and made a desperate effort to withdraw his arm. He only succeeded in disturbing his persecutor, which wound itself still tighter. It was supple as leather, strong as steel, cold as night. A second form - sharp, elongated, and narrow - issued out of the crevice, like a tongue out of monstrous jaws. It seemed to lick his naked body; then, suddenly stretching out, it became longer and thinner, as it crept over his skin, and wound itself round him. A terrible sense of anguish, comparable to nothing he had ever known, compelled all his muscles to contract. He felt upon his skin a number of flat, rounded points. It seemed as if innumerable suckers had fastened to his flesh, and were about to drink his blood. A third long, undulating shape issued from the hole in the rock, felt about his body, lashed round his ribs like a cord, and fixed itself there. There was sufficient light for Gilliatt to see the repulsive forms which had entangled themselves about him. A fourth ligature, but this one swift as an arrow, darted towards his stomach. These living things crept and glided about him; he felt the points of pressure, like sucking mouths, change their places from time to time. Suddenly a large, round, flattened, glutinous mass shot from beneath the crevice. It was the centre! The thongs were attached to it like spokes to the nave of a wheel. In the middle of this slimy mass appeared two eyes. The eyes were fixed on Gilliatt. He recognised the devil-fish. Gilliatt had but one resource - his knife. He knew that these frightful monsters are vulnerable in only one point - the head. Standing half naked in the water, his body lashed by the foul antennae of the devil-fish, Gilliatt looked at the devil-fish and the devilfish looked at Gilliatt. With the devil-fish, as with a furious bull, there is a certain moment in the conflict which must be seized. It is the instant when the bull lowers its neck; it is the instant when the devil-fish advances its head. The movement is rapid. He who loses that moment is destroyed. Suddenly it loosened another antenna from the rock, and darting it at him, seized him by the left arm. At the same moment it advanced its head. Rapid as was this movement, Gilliatt, by a gigantic effort, plunged the blade of his knife into the flat, slimy substance, and with a movement like the flourish of a whip, described a circle round the eyes and wrenched off the head as a man would draw a tooth. The four hundred suckers dropped at once from the man and the rock. The mass sank to the bottom of the water. Nearly exhausted, Gilliatt plunged into the water to heal by friction the numberless purple swellings which were pricking all over his body. He advanced up the recess. Something caught his eye. He approached nearer. The thing was a bleached skeleton; nothing was left but the white bones. Yes, something else. A leather belt and a tobacco-tin. On the belt Gilliatt read the name of Clubin; in the tobacco-tin, which he opened with his knife, he found three thousand pounds. When Gilliatt reached his sloop, with this belt and box in his possession, he found, to his unspeakable horror, that she had been making water fast. Had he come an hour later he would have found nothing above water but the funnel of the steamer. He slung a tarpaulin by chains overboard and hung it over the hole. Pressure of the sea held it tight. The wound was stanched. Gilliatt began to bale for dear life. As he emptied the hole the tarpaulin bulged in, as if a fist were pushing it from outside. He ran for his clothes; brought them, and stuffed them into the wound. He was saved - for a few moments. Death was certain. He had succeeded in the impossible, to fail in what a shipwright might have mended in a few minutes. Upon that solitary rock he had been subjected by turns to all the varied and cruel tortures of nature. He had conquered his isolation, conquered hunger, conquered thirst, conquered cold, conquered fever, conquered labour, conquered sleep. A dismal irony was then the end of all. Gilliatt climbed to the top of the rock and gazed wildly into space. He had no clothing. He stood naked in the midst of that immensity. Then, overwhelmed by the sense of that unknown infinity, like one bewildered by a strange persecution, confronting the shadows of night, in the midst of the murmur of the waves, the swell, the foam, the breeze, under that vast diffusion of force, having around him and beneath him the ocean, above him the constellations, under him the great unfathomable deep, he sank, gave up the struggle, laid down upon the rock, humbled, and uplifting his joined hands towards the terrible depths, he cried aloud, "Have mercy!" When he issued from his swoon, the sun was high in a cloudless sky. The blessed heat had saved the poor, broken, naked man upon the rock. He rose up refreshed, and filled with divine energy. A day's work sufficed to mend the gap in the sloop's side. On the following day, dressed in the tattered garments which had stuffed the rent, with a favourable breeze and a good sea, Gilliatt pushed off from the Douvres. IV. - Fate's Last Blow Gilliatt arrived in harbour at night. He went ashore in his rags, and hovered for a while about the darkness of Lethierry's house. Then he made his way into the garden, like an animal returning to its hole. He sat himself down and looked about him. He saw the garden, the pathways, the beds of flowers, the house, the two windows of Dérouchette's chamber. He felt it horrible to be obliged to breathe; he did what he could to prevent it. To see those windows was almost too much happiness for Gilliatt. Suddenly he saw her. Dérouchette approached. She stopped. She walked back a few paces, stopped again; then returned and sat upon a wooden bench. The moon was in the trees; a few clouds floated among the pale stars; the sea murmured to the shadows in an undertone. Gilliatt felt a thrill through him. He was the most miserable and yet the happiest of men. He knew not what to do. His delirious joy at seeing her annihilated him. He gazed upon her neck - her hair. A noise aroused them both - her from her reverie, him from his ecstasy. Someone was walking in the garden. It was the footsteps of a man. Dérouchette raised her eyes. The footsteps drew nearer, then ceased. Accident had so placed the branches that Dérouchette could see the newcomer while Gilliatt could not. He looked at Dérouchette. She was quite pale; her mouth was partly open, as with a suppressed cry of surprise. Her surprise was enchantment mingled with timidity. She seemed as if transfigured by that presence; as if the being whom she saw before her belonged not to this earth. The stranger, who was to Gilliatt only a shadow, spoke. A voice issued from the trees, softer than the voice of a woman; yet it was the voice of a man. Gilliatt heard many words, then, "Mademoiselle, you are poor; since this morning I am rich. Will you have me for your husband? I love you. God made not the heart of man to be silent. He has promised him eternity with the intention that he should not be alone. There is for me but one woman on the earth; it is you. I think of you as of a prayer. My faith is in God, and my hope in you." Gilliatt heard them talking - the woman he loved, the man whose shadow lay upon the path. Presently he heard the invisible man exclaim: "Mademoiselle! You are silent." "What would you have me say?" The man said, "I wait for your reply." "God has heard it," answered Dérouchette. Then she went forward; a moment afterwards, instead of one shadow upon the path, there were two. They mingled together, and became one. Gilliatt saw at his feet the embrace of those two shadows. Suddenly a noise burst forth at a distance. A voice was heard crying "Help!" and the harbour bell rang out on the night air. It was Lethierry ringing the bell furiously. He had wakened, and seen the funnel of the Durande in the harbour. The sight had driven him almost crazy. He rushed out crying "Help!" and pulling the great bell of the harbour. Suddenly he stopped abruptly. A man had just turned the corner of the quay. It was Gilliatt. Lethierry rushed at him, embraced him, hugged him, cried over him, and dragged him into the lower room of the Bravées. "Give me your word that I am not crazy!" he kept crying. "It can't be true. Not a tap, not a pin missing. It is incredible. We have only to put in a little oil. What a revolution! You are my child, my son, my Providence. Brave lad! To go and fetch my good old engine. In the open sea among those cut-throat rocks. I have seen some strange things in my life; nothing like that." Gilliatt gave him the belt and the box containing the three thousand pounds stolen by Clubin. Again Lethierry was thrown into a wild amazement. "Did anyone ever see a man like Gilliatt?" he concluded. "I was struck down to the ground, I was a dead man. He comes and sets me up again as firm as ever. And all the while I was never thinking of him. He had gone clean out of my mind; but I recollect everything now. Poor lad! Ah, by the way, you know you are to marry Dérouchette." Gilliatt leaned with his back against the wall, like one who staggers, and said, in a tone very low, but distinct, "No." Lethierry started. "How, no?" "I do not love her." Lethierry laughed that idea to scorn. He was wild with joy. Gilliatt, his son, his preserver, should marry Dérouchette - he, and none other. Neighbours had begun to flock in, roused by the bell. The room was crowded. Dérouchette presently glided in, and was espied by Lethierry in the crowd. He seized her; told her the news. "We are rich again! And you shall marry the prodigy who has done this thing." His eye fell upon the man who had followed Dérouchette into the room; it was the young priest whom Gilliatt had rescued from the seat in the rock. "Ah, you are there, Monsieur le Curé," exclaimed the old man; "you will marry these young people for us. There's a fine fellow!" he cried, and pointed to Gilliatt. Gilliatt's appearance was hideous. He was in the condition in which he had that morning set sail from the rocks - in rags, his bare elbows showing through his sleeves, his beard long, his hair rough and wild, his eyes bloodshot, his skin peeling, his hands covered with wounds, his feet naked and torn. Some of the blisters left by the devil-fish were still visible upon his arms. "This is my son-in-law!" cried Lethierry. "How he has struggled with the sea! He is all in rags. What shoulders! What hands! There's a splendid fellow!" But Lethierry did not know Gilliatt. The poor broken creature escaped from the room. He himself made all the arrangements for the marriage of the priest and Dérouchette; he placed the special license in their hands, secured a priest for the purpose, and secured passages for them in the ship waiting in the roads for England. When he had done all this, he made his way to the seat in the cliff, and sat there waiting to see the ship appear round the bight and disappear on the horizon. The ship appeared with the slowness of a phantom. Gilliatt watched it. Suddenly a touch and a sensation of cold caused him to look down. The sea had reached his feet. He lowered his eyes, then raised them again. The ship was quite near. The rock in which the rains had hollowed out this giant's seat was so completely vertical, and there was so much water at its base, that in calm weather vessels were able to pass without danger within a few cables' length. The ship was already abreast of the rock. Gilliatt could see the stir of life on the sunlit deck. The deck was as visible as if he had stood upon it. He saw bride and bridegroom sitting side by side, like two birds, warming themselves in the noonday sun. A celestial light was in those two faces formed by innocence. The silence was like the calm of heaven. The vessel passed. He watched her till her masts and sails formed only a white obelisk, gradually decreasing against the horizon. He felt that the water had reached his waist. Sea-mews and cormorants flew about him restlessly, as if anxious to warn him of his danger. The ship was rapidly growing less. There was no foam around the rock where he sat; no wave beat against its granite sides. The water rose peacefully. It was nearly level with Gilliatt's shoulders. The birds were hovering about him, uttering short cries. Only his head was now visible. The tide was nearly at the full. Evening was approaching. Gilliatt's eyes continued fixed upon the vessel on the horizon. Their expression resembled nothing earthly. A strange lustre shone in their calm and tragic depths. There was in them the peace of vanished hopes, the calm but sorrowful acceptance of an end far different from his dreams. By degrees the dusk of heaven began to dawn in them, though gazing still upon the point in space. At the same moment the wide waters round the rock and the vast gathering twilight closed upon them. At the moment when the vessel vanished on the horizon, the head of Gilliatt disappeared. Nothing now was visible but the sea. |