|

|

The Symposium ... Squashed down to read in about 15 minutes "...of all the gods, Love is the eldest and the most to be honoured"   Wikipedia - Wikipedia -  Full Text - Full Text -  Print Edition: ISBN 0872206335 Print Edition: ISBN 0872206335

The Symposium is a discussion on the nature of love, in the form of a series of speeches, both satirical and serious, given by a group of men at a symposium or drinking party at the house of the tragedian Agathon at Athens. The setting seems realistic, the context credible and the dialogue believable, so it may well be a record of a real discussion from more than two thousand years ago.

This version is largely based on the condensed version first published by Sir John Hammerton in 1919. It reduces the original 65,000 words down to around 2,700, or about 4%

The Symposium "...of all the gods, Love is the eldest and the most to be honoured" We were all a bit drunk at Agathon's house, and decided to talk about Love. Phaedrus said: Not birth, nor wealth, nor honours, nor aught else shall so inspire a man as Love. There is none so base but that Love may breathe into him the spirit of a hero. Therefore I say that, of all the gods, Love is the eldest and the most to be honoured. Pausanias said: There is more than one Love. Vulgar love is worthless, inconsistent and fleeting; but the love of the virtuous character abides throughout life. Aristophanes said: I have a theory that the gods split us in halves, and each each of us is always looking for his other half. Some seek the opposite sex to love, some seek the same (men who seek men are especially valiant and fine) but all are really craving to become one, soul and body. Agathon: These are love's gifts, but the God of Love himself is the youngest and the swiftest, since he outstrips in flight old age. Said Socrates: Is Love of something lacking? The prophetess Diotima told me that Love is not a mortal, nor a god. Love, in reality is of every good, not of just missing things or desired things. Aristodemus fell asleep, and woke to find Socrates, Aristophanes and Agathon still talking and drinking.

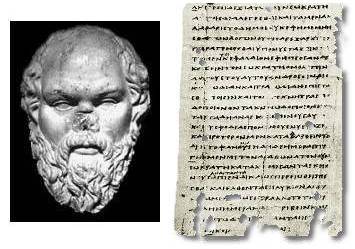

Plato of Athens c350BC Squashed version edited by Glyn Hughes © 2011 I - THE ORIGIN AND OPENING OF THE DEBATE THIS discussion took place a long time ago; I had my report of it from Aristodemus, a great admirer of Socrates, who was present. He told me that he met Socrates, looking unusually smart, and asked where he was going. "To dine with Agathon," said Socrates, whom Aristodemus then accompanied, by his invitation. On the way Socrates stopped, and told him to go on in front. On reaching Agathon's house he was hospitably welcomed to supper, and then discovered that Socrates had not arrived. He had taken up his stand in a neighbouring porch, and quite declined to come in till supper was half over. Besides Agathon, Phaedrus, Pausanias, Eryximachus, Aristophanes and others were present. When supper was over, the company resolved unanimously to limit its potations, as most of them were suffering from the previous night's excesses, except Socrates, who was equally prepared to drink everything or nothing, being quite invincible by liquor; and, instead of drinking, to debate on a subject to be proposed by Eryximachus. "My plan," said Eryximachus, "is really the plan of Phaedrus, not mine. He is always complaining that psalms and hymns are addressed to all the other gods, but none to Love, who is so mighty a god. So my plan is that everyone shall speak his best in the praise of Love, beginning with Phaedrus." "No one present can possibly vote against you," said Socrates. "Certainly not I, who avow myself to know nothing about any other subject, nor Agathon, nor Pausanias, nor very assuredly, Aristophanes, who is an unfailing devotee of Aphrodite and Dionysius." The company again agreed unanimously, and Phaedrus opened his discourse. "A great god is Love, worthy to be admired of gods and men. Moreover, he is the source of our greatest blessings. For to youth there can be none greater than a true lover and a true love. Not birth, nor wealth, nor honours, nor aught else shall so inspire a man as Love with all that makes life worthy, shame of base deeds, and noble emulation. For to be shamed before parents and companions is less bitter to a man than disgrace in the eyes of his beloved, or of a comrade to whom he is devoted. So that comrades in this kind would far sooner die than desert one another in peril. "There is none so base but that Love may breathe into him the spirit of a hero. Love alone makes men ready to die for another's sake; and not men only, but women. And to prove this we need but to look at Alectis, the daughter of Pelias, who, for her husband's sake was willing to die, so greatly her love exceeded that of his father and mother. Which deed the gods themselves did so approve that they suffered her soul to be released from Hades, a thing granted most rarely. Therefore I say that, of all the gods, Love is the eldest and the most to be honoured, and he that in life and in death helps men most to the possession of virtue and happiness." After Phaedrus had ended, and some others, Pausanias began. "This would be well enough if Love were one, but there is more than one Love. As there is that elder heavenly Aphrodite, motherless daughter of Heaven, and that goddess of the vulgar, daughter of Zeus and Dione, so there is a heavenly Love and a vulgar Love. The worthy Love is that which invites us to love worthily. The one is sensual, of the flesh; the other of the mind, freeing us from all wantonness. Now, it is most honourable to love the most excellent, even though they be less fair than others. And to win love is honourable, and to be rejected is shameful; wherefore all manner of devices are permitted to the wooer such as are permitted to none seeking another goal; yet in the lover they have a certain grace and may be done without dishonour. "But honour and dishonour lie not in the love itself, but in the manner of loving, whether it be done worthily. For the vulgar love is worthless, inconsistent and fleeting; but the love of the virtuous character abides throughout life." II - ARISTOPHANES THEORY OF SEXUALITY THE next to speak should have been Aristophanes; but he being afflicted with a hiccough, Eryximachus took up the tale. He seemed to identify love with harmony in the physical organization. "I don't know why the harmony of my physical organization should demand such a noisy operation as sneezing," said Aristophanes; "my hiccough departed when I sneezed. However, I am not going to follow the lead of Pausanias and Eryximachus. If man understood the power of Love, he would have more temples and more homage than all the other gods, yet he gets none. I will unfold it. We must begin with the nature of man, which has changed. First of all there was a third sex, the androgynous, combining the two, with four arms and legs, and the rest to match. Men had become very strong, and troublesome to the Olympian gods, yet they could not afford to annihilate them; so Zeus resolved to cut them in half to humble them. He declared that they shall walk upright on two legs, but each forever desiring his other half, so they will come together, and throwing their arms about one another, be entwined in mutual embraces, longing to grow into one. Each of us when separated is always looking for his other half. Men who are a section of that Androgynous double nature are lovers of women. Women who are a section of the woman do not care for men, but have female attachments. But they who are a section of the male seek the company of men, and embrace them. Such men are not shameless, as some say, but are valiant and manly, and grow to become our statesmen. When they reach manhood they are not naturally inclined to marry but are satisfied to live with one another in love. What real lovers are really craving for is to become really one, soul and body, with their other half. But if we fail in piety, we are in danger of being quartered instead." Agathon was arrested in a discussion into which Socrates was beguiling him, and entered in turn on his discourse. "We have been describing Love's gifts instead of praising Love himself - of all the gods the happiest, the most excellent and the most beautiful. He is the most beautiful of all, for he is the youngest of all and the swiftest, since he outstrips in flight old age, which is hateful to him. "For Love's virtue and power, mark that no violence is used by him, nor touches him; and he is most temperate, for he is stronger than all delights and desires. In courage Ares cannot match him, for he is master of Ares, who is possessed by the love of Aphrodite. Justice, then, and temperance and courage are his; and it remains to speak of his wisdom. First, then, I praise him as being myself a poet, just as Eryximachus praised him as a physician; for he is a poet so mighty that he can make a poet of him who was none before, and none can teach that which he knows not himself. His is the poesy of creation; Apollo himself was Love's pupil. "Of old, necessity ruled among the gods, and fearful things were done. But when Love was born all blessings came with him. He brings peace among men, calm upon the sea, repose and sleep in sadness. He frees us from ill-will, and fills us with kindliness, brings all gentleness and expels all ungentleness, whom every man should follow with sweet hymns in his praise, taking his part in that song of beauty which Love sings, healing the troubles of all minds of gods and men." III - SOCRATES DISCOURSES ON THE IMMORTALITY OF LOVE WHEN the applause subsided, "I was justified in my fears," said Socrates. "After a discourse of such consummate eloquence, how shall I say anything that will be listened to? I said I knew something about Love; but then I thought we were going to speak the truth on the subject; to give Love the honour which is his due; whereas the question has become one of seeing how we can praise Love most eloquently without regard to facts, and that is an art in which I am quite unskilled. But if you are content with mere truths expressed as they occur to me at the moment - " Phaedrus bade him speak in whatever fashion he chose. "Then, may I ask Agathon a few questions?" "Certainly." "Is Love love of something, or of nothing? A father is father of his child. A brother is brother of his brother and sister. Is Love in like manner love of something?" "Certainly." "It desires that of which it is the love, not possessing it?" "Yes." "When it no longer lacks, it no longer desires?" "I suppose not." "Well, then, Love is of something that it lacks. But you would have it that Love loves beauty; therefore it lacks beauty; therefore it is not beautiful. And the same argument applies to goodness as to beauty! However, let me tell you what the prophetess Diotima told me, for I have borrowed my argument from her, since I was arguing with her very much as Agathon has been doing just now. "What is not beautiful or good, need not, therefore, be ugly or bad, just as there is a state of mind which is neither knowledge nor ignorance, but correct opinion. So Love is not a mortal, nor a god, since we have seen that he does not possess all beauty and goodness and happiness, which we must acknowledge the gods to possess, but is something intermediate, a daemon, interpreting between the divine and the human. Love is one of many such intermediaries. As to his birth, Plenty was his sire and Poverty his mother; he partakes of the nature of each. As the gods do not seek wisdom, since they imagine that they have it, but only the philosophers, who are neither of these; so Love is of necessity a philosopher, thirsting for wisdom as for all forms of beauty. Your mistake was in taking Love to be not the lover, but the beloved. "LOVE, you say, desires the possession of beautiful things. What will he possess? The happy are happy in the possession of good things. Everyone desires to possess good things. But we do not admit that everyone loves, because we have selected a specific form of love, and chosen to apply to the species the name of a universal; just as every maker is properly a poet, but we have appropriated the name to a particular species of makers. Love, in reality is of every good, not of the missing half of oneself; desire that it should be ever present with it. It acts as the desire of generation in the beautiful, in relation both to body and soul, a something immortal in mortality as it were; not of the beautiful; but of immortality, necessarily, without which nothing can be ever present. "As for the phenomena of Love permeating all the living creation, they express the mortal nature seeking to become deathless by the one possible process of generation. For the mortal achieves immortality by the constant replacing of that which perishes, not by its separate continuity. So this Love is a tendency towards eternity and great deeds done for the immortality they bring. Sexual love is the expression of this craving for immortality in the physical organism; the work of all creative art is its intellectual issue, and especially of that political wisdom which we call moderation and justice. In whatsoever field this desire of immortality by propagation moves us, we must be attracted by the beautiful, and by beauty of soul more divinely than by beauty of form. But the children of the intellect are more desirable than the children of the body; for the former may bring the reward even of divine honours, but not the latter. "He who would love rightly must from the beginning seek to hold intercourse with beautiful forms, and love one, wherein he would generate intellectual beauty. But the beauty in all forms is one, and his love of beauty in form would be divided among many forms; whereas beauty in the soul being more excellent, one beautiful soul would suffice him even though the beauty of the form withered. Thus he would be led up to the contemplation of universal beauty, and the one science thereof. The beauty thus revealed is eternal, without beginning at all times, and utterly, and to all. This is that to which they attain who advance by these steps from the contemplation of beauty in particulars to the revelation of the supreme beauty. Such a one is at last in contact not with shadows but with the ultimate reality, and if immortality be at all given to human beings, he is thereby become immortal." IV - ALCIBIADES EULOGISES SOCRATES BUT now there came a clamour of revellers, and the voice of Alcibiades without, calling for Agathon; and then he came in, very drunk. "Drunk I am," said he, "but I'll drink with you. If you won't, we'll crown Agathon and depart." Being bidden to come in, he dropped down by Agathon, and then discovered that Socrates was on his other side. "Heracles!" he cried, "wherever I go, Socrates is lying in wait for me." "Protect me, Agathon," said Socrates, "I dare not speak to or look at anyone else when he is near, he is so jealous. I entreat you to reconcile us." "I won't be reconciled," said Alcibiades. "But I'll crown him too. He is always victor, not once in a way like Agathon yesterday." And this he did. "Our business," said Eryximachus, "is to speak in praise of Love; it is your turn." "Socrates won't let me praise anyone but Socrates. I won't praise anyone else. Shall I attack him? May I speak the truth about him? I cannot be methodical in this condition; I must say the things as they come into my head. "In the first place, he is just like a statue, the statue of the satyr Marsyas. Only, Socrates charms us by words instead of by musical pipings like him. Pericles and the rest cannot move me so; he even makes me ashamed of myself, till life ceases to be worth living, and I could wish to be quit of him altogether, only that would be worse. In spite of his professions, he cares no more for beauty than for any other external possessions, but when you get inside this Silenus, the divine images displayed are perfectly beautiful, and divine and wonderful. "We messed together in camp before Potidaea. He was far the hardiest of us all; scanty fair, plenty, intolerable cold never disturbed him. In the rout of Delium he was a sight to behold. I was mounted; he was trudging off the field with Laches on foot; but he was so majestically calm that anyone could see he would make a desperate resistance if attacked; so no one ventured. The fact is, Socrates is like no one else that ever was - excepting the Silene and Satyrs; rude, not to say absurd, outside, but inside full of every conceivable excellence." THERE was great laughter over the frankness of Alcibiades. However just then a fresh batch of revellers broke in. Eryximachus and Phaedrus went off to bed. Aristodemus fell asleep, and woke to find Socrates, Aristophanes and Agathon still talking and drinking, while Socrates was compelling the two dramatists to admit, against their convictions, that tragedy and comedy are a single art proper to one person. They went to sleep at last, and Socrates went away.  Socrates 471BC-399BC Plato of Athens c424-348BC Socrates was forced to commit suicide by poison for 'Corrupting the youth of Athens with new ideas' His last resting place is unknown. Plato went on to found an influential School. |