|

|

|

|

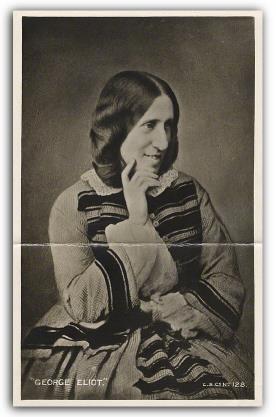

by 'George Eliot' (Mary Ann Evans) The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (1859) Mary Ann Evans ("George Eliot") was born Nov. 22, 1819, at South Farm, Arbury, Warwickshire, England, where her father was agent on the Newdigate estate. Mary established herself as one of the leading novelists of the Victorian era using the male pen name 'George Eliot' she said to ensure her works were taken seriously, but possibly also to shield her identity and hide her close relationship with the married George Henry Lewes. Abridged: JH/GH For more works by George Eliot, see The Index In the roomy workshop of Mr. Jonathan Burge, carpenter and builder, in the village of Hayslope, on the eighteenth of June, 1799, five workmen were busy upon doors and window-frames. The tallest of the five was a large-boned, muscular man, nearly six feet high. The sleeve rolled up above the elbow showed an arm that was likely to win the prize for feats of strength; yet the long, supple hand, with its broad finger tips, looked ready for works of skill. In his tall stalwartness Adam Bede was a Saxon, and justified his name. The face was large and roughly hewn, and when in repose had no other beauty than such as belongs to an expression of good-humoured, honest intelligence. It is clear at a glance that the next workman is Adam's brother. He is nearly as tall; he has the same type of features. But Seth's broad shoulders have a slight stoop, and his glance, instead of being keen, is confiding and benignant. The idle tramps always felt sure they could get a copper from Seth; they scarcely ever spoke to Adam. At six o'clock the men stopped working, and went out. Seth lingered, and looked wistfully at Adam, as if he expected him to say something. "Shalt go home before thee go'st to the preaching?" Adam asked. "Nay, I shan't be home before going for ten. I'll happen see Dinah Morris safe home, if she's willing. There's nobody comes with her from Poyser's, thee know'st." Adam set off home, and at a quarter to seven Seth was on the village green where the Methodists were preaching. The people drew nearer when Dinah Morris mounted the cart which served as a pulpit. There was a total absence of self-consciousness in her demeanour; she walked to the cart as simply as if she were going to market. There was no keenness in the eyes; they seemed rather to be shedding love than making observations. When Dinah spoke it was with a clear but not loud voice, and her sincere, unpremeditated eloquence held the attention of her audience without interruption. When the service was over, Seth Bede walked by Dinah's side along the hedgerow path that skirted the pastures and corn-fields which lay between the village and the Hall Farm. Seth could see an expression of unconscious placid gravity on her face - an expression that is most discouraging to a lover. He was timidly revolving something he wanted to say, and it was only when they were close to the yard-gates of the Hall Farm he had the courage to speak. "It may happen you'll think me overbold to speak to you again after what you told me o' your thoughts. But it seems to me there's more texts for your marrying than ever you can find against it. St. Paul says, 'Two are better than one,' and that holds good with marriage as well as with other things. For we should be o' one heart and o' one mind, Dinah. I'd never be the husband to make a claim on you as could interfere with your doing the work God has fitted you for. I'd make a shift, and fend indoor and out, to give you more liberty - more than you can have now; for you've got to get your own living now, and I'm strong enough to work for us both." When Seth had once begun to urge his suit, he went on earnestly and almost hurriedly. His voice trembled at the last sentence. They had reached one of those narrow passes between two tall stones, which performed the office of a stile in Loamshire. And Dinah paused, and said, in her tender but calm notes, "Seth Bede, I thank you for your love towards me, and if I could think of any man as more than a Christian brother, I think it would be you. But my heart is not free to marry, or to think of making a home for myself in this world. God has called me to speak His word, and He has greatly owned my work." They said farewell at the yard-gate, for Seth wouldn't enter the farmhouse, choosing rather to turn back along the fields through which he and Dinah had already passed. It was ten o'clock when he reached home, and he heard the sound of tools as he lifted the latch. "Why, mother," said Seth, "how is it as father's working so late?" "It's none o' thy feyther as is a-workin'; it's thy brother as does iverything, for there's niver nobody else i' th' way to do nothin'." Lisbeth Bede was going on, for she was not at all afraid of Seth - who had never in his life spoken a harsh word to his mother - and usually poured into his ears all the querulousness which was repressed by the awe which mingled itself with her idolatrous love of Adam. But Seth, with an anxious look, had passed into the workshop, and said, "Addy, how's this? What! Father's forgot the coffin?" "Ay, lad, th' old tale; but I shall get it done," said Adam, looking up. "Why, what's the matter with thee - thee'st in trouble?" Seth's eyes were red, and there was a look of deep depression on his mild face. "Yes, Addy, but it's what must be borne, and can't be helped. Let me take my turn now, and do thee go to bed." "No, lad; I'd rather go on, now I'm in harness. The coffin's promised to be ready at Brox'on by seven o'clock to-morrow morning. I'll call thee up at sunrise, to help me to carry it when it's done. Go and eat thy supper and shut the door, so as I mayn't hear mother's talk." Adam worked throughout the night, thinking of his childhood and its happy days, and then of the days of sadness that came later when his father began to loiter at public-houses, and Lisbeth began to cry at home. He remembered well the night of shame and anguish when he first saw his father quite wild and foolish. The two brothers set off in the early sunlight, carrying the long coffin on their shoulders. By six o'clock they had reached Broxton, and were on their way home. When they were coming across the valley, and had entered the pasture through which the brook ran, Seth said suddenly, beginning to walk faster, "Why, what's that sticking against the willow?" They both ran forward, and dragged the tall, heavy body out of the water; and then looked with mute awe at the glazed eyes - forgetting everything but that their father lay dead before them. Adam's mind rushed back over the past in a flood of relenting and pity. Only a few hours ago, and the gray-haired father, of whom he had been thinking with a sort of hardness as certain to live to be a thorn in his side, was perhaps even then struggling with that watery death! It is a very fine old place of red brick, the Hall Farm - once the residence of a country squire, and the Hall. Plenty of life there, though this is the drowsiest time of the year, just before hay-harvest; and it is the drowsiest time of the day, too, for it is half-past three by Mrs. Poyser's handsome eight-day clock. Mrs. Poyser, a good-looking woman, not more than eight-and-thirty, of fair complexion and sandy hair, well shaped, light-footed, had just taken up her knitting, and was seated with her niece, Dinah Morris. Another motherless niece, Hetty Sorrel, a distractingly pretty girl of seventeen, was busy in the adjoining dairy. "You look the image o' your aunt Judith, Dinah, when you sit a-sewing," said Mrs. Poyser. "I allays said that o' Judith, as she'd bear a pound weight any day to save anybody else carrying a ounce. And it made no difference in her, as I could see, when she took to the Methodists; only she talked a bit different, and wore a different sort o' cap. If you'd only come and live i' this country you might get married to some decent man, and there'd be plenty ready to have you, if you'd only leave off that preaching, as is ten times worse than anything your Aunt Judith ever did. And even if you'd marry Seth Bede, as is a poor, wool-gathering Methodist, and's never like to have a penny beforehand, I know your uncle 'ud help you with a pig, and very like a cow, for he's allays been good-natur'd to my kin, for all they're poor, and made 'em welcome to the house; and 'ud do for you, I'll be bound, as much as ever he'd do for Hetty, though she's his own niece." The arrival of Mr. Irwine, the rector of Hayslope, and Captain Donnithorne, Squire Donnithorne's grandson and heir, interrupted Mrs. Poyser's flow of talk. "I'll lay my life they're come to speak about your preaching on the Green, Dinah. It's you must answer 'em, for I'm dumb. I've said enough a'ready about your bringing such disgrace upo' your uncle's family. I wouldn't ha' minded if you'd been Mr. Poyser's own niece. Folks must put up wi' their own kin as they put up wi' their own noses; it's their own flesh and blood." Mr. Irwine, however, was the last man to feel any annoyance at the Methodist preaching, and young Arthur Donnithorne's visit was merely an excuse for exchanging a few words with Hetty Sorrel. The rector mentioned before he left that Thias Bede had been found drowned in the Willow Brook; and Dinah Morris at once decided that she might be of some comfort to the widow, and set out for the village. As for Hetty Sorrel, she was thinking more of the looks Captain Donnithorne had cast at her than of Adam and his troubles. Bright, admiring glances from a handsome young gentleman - those were the warm rays that set poor Hetty's heart vibrating. Hetty was quite used to the thought that people liked to look at her. She was aware that Mr. Craig, the gardener at Squire Donnithorne's, was over head-and-ears in love with her. She knew still better that Adam Bede - tall, upright, clever, brave Adam Bede - who carried such authority with all the people round about, and whom her uncle was always delighted to see of an evening, saying that "Adam knew a fine sight more o' the natur o' things than those as thought themselves his betters" - she knew that this Adam, who was often rather stern to other people, and not much given to run after the lassies, could be made to turn pale or red any day by a word or a look from her. Hetty's sphere of comparison was not large, but she couldn't help perceiving that Adam was "something like" a man; always knew what to say about things; knew, with only looking at it, the value of a chestnut-tree that was blown down, and why the damp came in the walls, and what they must do to stop the rats; and wrote a beautiful hand that you could read, and could do figures in his head - a degree of accomplishment totally unknown among the richest farmers of that country-side. Hetty was quite certain her uncle wanted her to encourage Adam, and would be pleased for her to marry him. For the last three years - ever since he had superintended the building of the new barn - Adam had always been made welcome at the Hall Farm, and for the last two years at least Hetty had been in the habit of hearing her uncle say, "Adam Bede may be working for a wage now, but he'll be a master-man some day, as sure as I sit in this chair. Master Burge is in the right on't to want him to go partners and marry his daughter, if it's true what they say. The woman as marries him 'ull have a good take, be't Lady Day or Michaelmas," a remark which Mrs. Poyser always followed up with her cordial assent. "Ah," she would say, "it's all very fine having a ready-made rich man, but may happen he'll be a ready-made fool; and it's no use filling your pocket full of money if you've got a hole in the corner. It'll do you no good to sit in a spring-cart o' your own if you've got a soft to drive you; he'll soon turn you over into the ditch." But Hetty had never given Adam any steady encouragement. She liked to feel that this strong, keen-eyed man was in her power; but as to marrying Adam, that was a very different affair. Hetty's dreams were all of luxuries. She thought if Adam had been rich, and could have given the things of her dreams - large, beautiful earrings and Nottingham lace and a carpeted parlour - she loved him well enough to marry him. The last few weeks a new influence had come over Hetty; she had become aware that Mr. Arthur Donnithorne would take a good deal of trouble for the chance of seeing her. And Dinah Morris was away, preaching and working in a manufacturing town. Adam Bede, like many other men, thought the signs of love for another were signs of love towards himself. The time had come to him that summer, as he helped Hetty pick currants in the orchard of the Hall Farm, that a man can least forget in after-life - the time when he believes that the first woman he has ever loved is, at least, beginning to love him in return. He was not wrong in thinking that a change had come over Hetty; the anxieties and fears of a first passion with which she was trembling had become stronger than vanity, and while Adam drew near to her she was absorbed in thinking and wondering about Arthur Donnithorne's possible return. For the first time Hetty felt that there was something soothing to her in Adam's timid yet manly tenderness; she wanted to be treated lovingly. And Arthur was away from home; and, oh, it was very hard to bear the blank of absence. She was not afraid that Adam would tease her with love-making and flattering speeches; he had always been so reserved to her. She could enjoy without any fear the sense that this strong, brave man loved her and was near her. It never entered into her mind that Adam was pitiable, too, that Adam, too, must suffer one day. It was from Adam that she found out that Captain Donnithorne would be back in a day or two, and this knowledge made her the more kindly disposed towards him. But for all the world Adam would not have spoken of his love to Hetty yet, till this commencing kindness towards him should have grown into unmistakable love. He did no more than pluck a rose for her, and walk back to the farm with her arm in his. When Adam, after stopping a while to chat with the Poysers, had said good-night, Mr. Poyser remarked, "If you can catch Adam for a husband, Hetty, you'll ride i' your own spring-cart some day, I'll be your warrant." Her uncle did not see the little toss of the head with which Hetty answered him. To ride in a spring-cart seemed a very miserable lot indeed to her now. It was on August 18, when Adam, going home from some work he had been doing at one of the farms, passed through a grove of beeches, and saw, at the end of the avenue, about twenty yards before him, two figures. They were standing opposite to each other with clasped hands, and they separated with a start at a sharp bark from Adam Bede's dog. One hurried away through a gate out of the grove; the other, Arthur Donnithorne, looking flushed and excited, sauntered towards Adam. The young squire had been home for some weeks celebrating his twenty-first birthday, and he was leaving on the morrow to rejoin his regiment. Hitherto there had been a cordial and sincere liking and a mutual esteem between the two young men; but now Adam stood as if petrified, and his amazement turned quickly to fierceness. Arthur tried to pass the matter off lightly, as if it had been a chance meeting with Hetty; but Adam, who felt that he had been robbed treacherously by the man in whom he had trusted, would not so easily let him off. It came to blows, and Arthur sank under a well-planted blow of Adam's, as a steel rod is broken by an iron bar. Before they separated, Arthur promised that he would write and tell Hetty there could be no further communication between them. And this promise he kept. Adam rested content with the assurance that nothing but an innocent flirtation had been stopped. As the days went by he found that the calm patience with which he had waited for Hetty's love had forsaken him since that night in the beech-grove. The agitations of jealousy had given a new restlessness to his passion. Hetty, for her part, after the first misery caused by Arthur's letter, had turned into a mood of dull despair, and sought only for change. Why should she not marry Adam? She did not care what she did so that it made some change in her life. So, in November, when Mr. Burge offered Adam a share in his business, Adam not only accepted it, but decided that the time had come to ask Hetty to marry him. Hetty did not speak when Adam got out the question, but his face was very close to hers, and she put up her round cheek against his, like a kitten. She wanted to be caressed - she wanted to feel as if Arthur were with her again. Adam only said after that, "I may tell your uncle and aunt, mayn't I, Hetty?" And she said "Yes." The red firelight on the hearth at the Hall Farm shone on joyful faces that evening when Adam took the opportunity of telling Mr. and Mrs. Poyser that he saw his way to maintaining a wife now, and that Hetty had consented to have him. There was a great deal of discussion before Adam went away about the possibility of his finding a house that would do for him to settle in. "Well, well," said Mr. Poyser at last, "we needna fix everything to-night. You canna think o' getting married afore Easter. I'm not for long courtships, but there must be a bit o' time to make things comfortable." This was in November. Then in February came the full tragedy of Hetty Sorrel's life. She left home, and in a strange village, a child - Arthur Donnithorne's child - was born. Hetty left the baby in a wood, and returned to find it dead. Arrest and trial followed, and only at the last moment was the capital sentence commuted to transportation. She died a few years later on her way home. It was the autumn of 1801, and Dinah Morris was once more at the Hall Farm, only to leave it again for her work in the town. Mrs. Poyser noticed that Dinah, who never used to change colour, flushed when Adam said, "Why, I hoped Dinah was settled among us for life. I thought she'd given up the notion o' going back to her old country." "Thought! Yes," said Mrs. Poyser; "and so would anybody else ha' thought as had got their right ends up'ards. But I suppose you must be a Methodist to know what a Methodist 'ull do. It's all guessing what the bats are flying after." "Why, what have we done to you, Dinah, as you must go away from us?" said Mr. Poyser. "It's like breaking your word; for your aunt never had no thought but you'd make this your home." "Nay, uncle," said Dinah, trying to be quite calm. "When I first came I said it was only for a time, as long as I could be of any comfort to my aunt." "Well, an' who said you'd ever left off being a comfort to me?" said Mrs. Poyser. "If you didna mean to stay wi' me, you'd better never ha' come. Them as ha' never had a cushion don't miss it." Dinah set off with Adam, for Lisbeth was ailing and wanted Dinah to sit with her a bit. On the way he reverted to her leaving the Hall Farm. "You know best, Dinah, but if it had been ordered so that you could ha' been my sister, and lived wi' us all our lives, I should ha' counted it the greatest blessing as could happen to us now." Dinah made no answer, and they walked on in silence, until presently, crossing the stone stile, Adam saw her face, flushed, and with a look of suppressed agitation. It struck him with surprise, and then he said, "I hope I've not hurt or displeased you by what I've said, Dinah; perhaps I was making too free. I've no wish different from what you see to be best; and I'm satisfied for you to live thirty miles off if you think it right." Poor Adam! Thus do men blunder. Lisbeth opened his eyes on the Sunday morning when Adam sat at home and read from his large pictured Bible. For a long time his mother talked on about Dinah, and about how they were losing her when they might keep her, and Adam at last told her she must make up her mind that she would have to do without Dinah. "Nay, but I canna ma' up my mind, when she's just cut out for thee; an' nought shall ma' me believe as God didna make her and send her here o' purpose for thee. What's it sinnify about her being a Methody? It 'ud happen wear out on her wi' marryin'." Adam threw himself back in his chair and looked at his mother. He understood now what her talk had been aiming at, and tried to chase away the notion from her mind. He was amazed at the way in which this new thought of Dinah's love had taken possession of him with an overmastering power that made all other feelings give way before the impetuous desire to know that the thought was true. He spoke to Seth, who said quite simply that he had long given up all thoughts of Dinah ever being his wife, and would rejoice in his brother's joy. But he could not tell whether Dinah was for marrying. "Thee might'st ask her," Seth said presently. "She took no offence at me for asking, and thee'st more right than I had." When Adam did ask, Dinah answered that her heart was strongly drawn towards him, but that she must wait for divine guidance. So she left the Hall Farm and went back to the town, and Adam waited, - and then went after her to get his answer. "Adam," she said when they had met and walked some distance together, "it is the divine will. My soul is so knit to yours that it is but a divided life I live without you. And this moment, now you are with me, and I feel that our hearts are filled with the same love, I have a fullness of strength to bear and do our Heavenly Father's will that I had lost before." Adam paused and looked into her sincere eyes. "Then we'll never part any more, Dinah, till death parts us." And they kissed each other with deep joy.  |