|

|

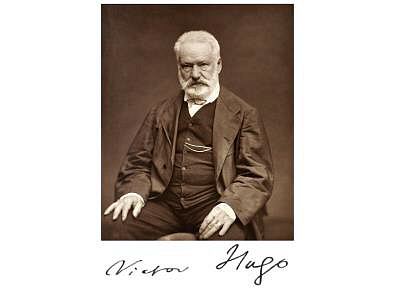

(L'Homme qui Rit) by Victor Hugo The original, squashed down to read in about 25 minutes  (Paris, 1831) Victor Marie Hugo was born on 26th February 1802 at the ancient city of Besançon in Eastern France. His political views were firm and radical, though somewhat variable. Hugo was elevated to the peerage by King Louis-Philippe, but his opposition to Louis Napoleon's seizing power in 1851 led to his exile in Jersey, from where he was, in turn, expelled for criticising Queen Victoria. He finally settled in Guernsey, returning to France in 1870 as a significant national hero. Abridged: JH/GH For more books by Victor Hugo, see The Index I. - The Child Ursus and Homo were old friends. Ursus was a man, Homo a wolf. The two went about together from town to town, from country-side to country-side. Ursus lived in a small van upon wheels which Homo drew by day and guarded by night. Ursus was a juggler, a ventriloquist, a doctor, and a misanthrope. He was also something of a poet. The wolf and he had grown old together. One bitterly cold night in January 1690, when Ursus and his van were at Weymouth, a small vessel put off from Portland. It contained a dozen people, and it left behind on the rock, and alone, a small boy. The people were called Comprachicos. They bought children, and understood how to mutilate and deform them, thus making them valuable for exhibition at fairs. But an act of parliament had just been passed to destroy the trade of the Comprachicos. Hence this flight from Portland, and the forsaking of the child. The vessel was wrecked and all on board perished off the coast of France, but not before one of the passengers had inscribed on a piece of parchment the name of the child and the name of a certain English prisoner who could identify the child. This parchment was sealed in a bottle and left to the waves. The child watched the disappearance of the boat. He was stupefied at finding himself alone; the men who had left him were the only people he had ever known, and they had failed him. He did not know where he was, but he knew that he must seek food and shelter. It was very cold and dark, and the boy was barefoot, but he made his way across Portland and the Chesil bank, and gained the mainland. He found in the snow a footprint, and set out to follow it. Presently he heard a groan, and came to the end of the footprints. The woman, a beggar-woman who had lost her way, had uttered the groan. She had sunk down in the snow, and was dead when the boy found her. He heard a cry, and discovered a baby, wretched with cold, but still alive, clinging to its dead mother's breast. The boy took the baby in his arms. Forsaken himself, he had heard the cry of distress, and wrapping the infant in his coat, he pursued his journey in the teeth of the freezing wind. Four hours had passed since the boat had sailed away; this baby was the first living person the boy had met. Struggling along with his burden, the boy reached Weymouth, then a hamlet, and a suburb of the town and port of Melcombe Regis. He knocked at doors and windows; no one stirred. For one thing, everybody was asleep, and those who were awakened by the knock were afraid of opening a window, for fear of some sick vagabond being outside. Suddenly the boy heard in the darkness a grinding of teeth and a growl. The silence was so dreadful that he was glad of the noise, and moved in the direction whence it came. He saw a carriage on wheels, with smoke coming out of the roof through a funnel, and a light within. Something perceived his approach and growled furiously and tugged at its chain. At the same time a head was put out of a window in the van. "Be quiet there!" said the head, and the noise ceased. "Is anyone there?" said the head again. "Yes, I," said the child. "You? Who are you?" "I am very tired and cold and hungry," said the child. "We can't all be as happy as a lord. Go away!" said the head, and the window was shut down. The child turned away in despair. But no sooner was the window shut than the door at the top of the steps opened, and the same voice called out from within the van, "Well, why don't you come in? What sort of a fellow is this who is cold and hungry, and who stays outside?" The boy climbed up the three steps with difficulty, carrying the baby, and hesitated for a moment at the door. On the ceiling was written in large letters: It was the house of Ursus the child had come to. Homo had been growling, Ursus speaking. The child made out near the stove an elderly man, who, as he stood, reached the roof of the caravan. "Come in! Put down your bundle!" said Ursus. "How wet you are, and half frozen! Take off those rags, you young villain!" He tore off the boy's rags, clothed him in a man's shirt and a knitted jacket, rubbed the boy's limbs and feet with a woollen rag, found there was nothing frost-bitten, and gave him his own scanty supper to eat. "I have worked all day and far into the night on an empty stomach," muttered Ursus, "and now this dreadful boy swallows up my food. However, it's all one. He shall have the bread, the potato, and the bacon, but I will have the milk." Just then the infant began to wail. Ursus fed it with the milk by means of a small bottle, took off the tatters in which it was wrapped, and swathed it in a large piece of dry, clean linen. When the boy had finished his supper, Ursus asked him who he was, but he could get no answer save that he had been abandoned that night. "But you must have relations, since you have this baby sister." "It is not my sister; it is a baby that I found." Ursus listened to the boy's story. Then he brought out an old bearskin, laid it on a chest, placed the sleeping infant on this, and told the boy to lie down beside the baby. Ursus rolled the bearskin over the children, tucked it under their feet, and went out into the night to see if the woman could be saved. He returned at dawn; his efforts had been fruitless. The boy had awakened at hearing Ursus, and for the first time the latter saw his face. "What are you laughing at? You are frightful! Who did that to you?" said Ursus. The boy answered, "I am not laughing. I have always been like this." Ursus turned away, and muttered, "I thought that sort of work was out of date." He took down an old book, and read in Latin that, by slitting the mouth and performing other operations in childhood, the face would become a mask whose owner would be always laughing. At that moment the infant awoke, and Ursus gave it what was left of the milk. The baby girl was blind. Ursus had already decided that he and Homo would adopt the two children. II. - Gwynplaine and Dea Gwynplaine was a mountebank. As soon as he exhibited himself all who saw him laughed. His laugh created the laughter of others, though he did not laugh himself. It was his face only that laughed, and laughed always with an everlasting laugh. Fifteen years had passed since the night when the boy came to the caravan at Weymouth, and Gwynplaine was now twenty-five. Ursus had kept the two children with him; the blind girl he called Dea. The boy said he had always been called Gwynplaine. Of course the two were in love. Gwynplaine adored Dea, and Dea idolised Gwynplaine. "You are beautiful," she would say to him. The crowd only saw his face; for Dea, Gwynplaine was the person who had saved her from the tomb, and who was always kind and good-tempered. "The blind see the invisible," said Ursus. The old caravan had given way to a great van - called the Green Box - drawn by a pair of stout horses. Gwynplaine had become famous. In every fair-ground the crowd ran after him. In 1705 the Green Box arrived in London and was established at Southwark, in the yard of the Tadcaster Inn. A placard was hung up with the following inscription, composed by Ursus: "Here can be seen Gwynplaine, deserted, when he was ten years old, on January 29, 1690, on the coast of Portland, by the rascally Comprachicos. The boy now grown up is known as 'The Man who Laughs.'" All Southwark came to see Gwynplaine, and soon people heard of him on the other side of London Bridge, and crowds came from the City to the Tadcaster Inn. It was not long before the fashionable world itself was drawn to the Laughing Man. One morning a constable and an officer of the High Court summoned Gwynplaine to Southwark Gaol. Ursus watched him disappear behind the heavy door with a heavy heart. Gwynplaine was taken down flights of stairs and dark passages till he reached the torture-chamber. A man's body lay on the ground on its back. Its four limbs, drawn to four columns by chains, were in the position of a St. Andrew's Cross. A plate of iron, with five or six large stones, was placed on the victim's chest. On a seat close by sat an old man - the sheriff of the county of Surrey. "Come closer," said the sheriff to Gwynplaine. Then he addressed the wretched man on the floor, who for four days, in spite of torture, had kept silence. "Speak, unhappy man. Have pity on yourself. Do what is required of you. Open your eyes, and see if you know this man." The prisoner saw Gwynplaine. Raising his head he looked at him, and then cried out, "That's him! Yes - that's him!" "Registrar, take down that statement," said the sheriff. The cry of the prisoner overwhelmed Gwynplaine. He was terrified by a confession that was unintelligible to him, and began in his distress to stammer and protest his innocence. "Have pity on me, my lord. You have before you only a poor mountebank - " "I have before me," said the sheriff, "Lord Fermain Clancharlie, Baron Clancharlie and Hunkerville, and a peer of England!" Then the sheriff, rising, offered his seat with a bow to Gwynplaine, saying, "My lord, will you please to be seated?" III. - The House of Lords Before he left the prison the sheriff explained to Gwynplaine how it was he was Lord Clancharlie. The bottle containing the documents which had been thrown into the sea in January 1690 had at last come to shore, and had been duly received at the Admiralty by a high official named Barkilphedro. This document declared that the child abandoned by those on the sinking vessel was the only child of Lord Fermain Clancharlie, deceased. At the age of two it had been sold, disfigured, and put out of the way by order of King James II. Its parents were dead, and a man named Hardquanonne, now in prison at Chatham, had performed the mutilation, and would recognise the child, who was called Gwynplaine. Being about to die, the signatories to the document confessed their guilt in abducting the child, and could not, in the face of death, refrain from acknowledgment of their crime. The prisoner Hardquanonne had been found at Chatham, and he had recognised Gwynplaine. Hardquanonne died of the tortures he had suffered, but just before his death he said, "I swore to keep the secret, and I have kept it as long as I could. We did it between us - the king and I. Silence is no longer any good. This is the man." What was the reason for the hatred of James II. to the child? This. Lord Clancharlie had taken the side of Cromwell against Charles I., and had gone into exile in Switzerland rather than acknowledge Charles II. as king. On the death of this nobleman James II. had declared his estates forfeit, and the title extinct, believing that the heir was lost beyond possible recovery. On David Dirry-Moir, an illegitimate son of Lord Clancharlie, were the peerage and estates conferred, on condition that he married a certain Duchess Josiana, an illegitimate daughter of James II. How was it Gwynplaine was restored to his inheritance? Anne was Queen of England when the bottle was taken to the Admiralty in 1705, and shared with the high official whose business it was to attend to all flotsam and jetsam, a cordial dislike of Duchess Josiana. It seemed to the Queen an excellent thing that Josiana should have to marry this frightful man, and as for David Dirry-Moir he could be made an admiral. Anne consulted the Lord Chancellor privately, and he strongly advised, without blaming James II., that Gwynplaine must be restored to the peerage. Gwynplaine, without having time to return to the Green Box, was carried off by Barkilphedro to one of his country houses, near Windsor, and bidden the next day take his seat in the House of Lords. He had entered the terrible prison in Southwark expecting the iron collar of a felon, and he had placed on his head the coronet of a peer. Barkilphedro had told him that a man could not be made a peer without his own consent; that Gwynplaine, the mountebank, must make room for Lord Clancharlie, if the peerage was accepted; and he had made his decision. On awakening the next morning he thought of Dea. Then came a royal summons to appear in the House of Lords, and Gwynplaine returned to London in a carriage provided by the queen. The secret of his face was still unknown when he entered the House of Lords, for the Lord Chancellor had not been informed of the nature of the deformation. The investiture took place on the threshold of the House, then very ill-lit, and two very old and half-blind noblemen acted as sponsors at the Lord Chancellor's request. The whole ceremony was enacted in a sort of twilight, for the Lord Chancellor was anxious to avoid any sensation. In less than half an hour the sitting was full. Gossip was already at work about the new Lord Clancharlie. Several peers had seen the Laughing Man, and they now heard that he was already in the Upper House; but no one noticed him until he rose to speak. His face was terrible, and the whole House looked with horror upon him. "What does all this mean?" cried the Earl of Wharton, an old and much respected peer. "Who has brought this man into the House? Who are you? Where do you come from?" Gwynplaine answered, "I come from the depths. I am misery. My lords, I have a message for you." The House shuddered, but listened, and Gwynplaine continued. "My lords, among you I am called Lord Fermain Clancharlie, but my real name is one of poverty - Gwynplaine. I have grown up in poverty; frozen by winter, and made wretched by hunger. Yesterday I was in the rags of a clown. Can you realise what misery means? Before it is too late try and understand that our system of society is a false one." But the House rocked with uncontrollable laughter at the face of Gwynplaine. In vain he pleaded with those who sat around him not to laugh at misery. They refused to listen, and the sitting broke up in confusion, the Lord Chancellor adjourning the House. Gwynplaine went out of the House alone. IV. - Night and the Sea Ursus waited for some time after seeing Gwynplaine disappear within Southwark Gaol, then he returned sadly to Tadcaster Inn. That very night the corpse of Hardquanonne was brought out from the gaol and buried in the cemetery hard by, and Ursus, who had returned to the prison gate, watched the procession, and saw the coffin carried to the grave. "They have killed him! Gwynplaine, my son, is dead!" cried Ursus, and he burst into tears. The following morning the sheriff's officer, accompanied by Barkliphedro, waited on Ursus, and told him he must leave Southwark, and leave England. The last hope in the soul of Ursus died when Barkilphedro said gravely that Gwynplaine was dead. Ursus bent his head. The sentence on Gwynplaine had been executed - death. His sentence was pronounced - exile. Nothing remained for Ursus but to obey. He felt as if in a dream. Within two hours Ursus, Homo, and Dea were on board a Dutch vessel which was shortly to leave a wharf at London Bridge. The sheriff ordered the Tadcaster Inn to be shut up. Gwynplaine found the vessel. He had left the House of Lords in despair. He had made his effort, and the result was derision. The future was terrible. Dea was his wife, he had lost her, and he would be spurned by Josiana. He had lost Ursus, and gained nothing but insult. Let David take the peerage; he, Gwynplaine, would return to the Green Box. Why had he ever consented to be Lord Clancharlie? He wandered from Westminster to Southwark, only to find the Tadcaster Inn shut up, and the yard empty. It seemed he had lost Ursus and Dea for ever. He turned and gazed into the deep waters by London Bridge. The river in its darkness offered a resting place where he might find peace. He got ready to mount the masonry and spring over, when he felt a tongue licking his hands. He turned, and Homo was behind him. Gwynplaine uttered a cry. Homo wagged his tail. Then the wolf led the way down a narrow platform to the wharf, and Gwynplaine followed him. On the vessel alongside the wharf was the old wooden tenement, very worm-eaten and rotten now, in which Ursus lived when the boy first came to him at Weymouth. Gwynplaine listened. It was Ursus talking to Dea. "Be calm, my child. All will come right. You do not understand what it is to rupture a blood-vessel. You must rest. To-morrow we shall be at Rotterdam." "Father," Dea answered, "when two beings have always been together from infancy, and that state is disturbed, death must come. I am not ill, but I am going to die." She raised herself on the mattress, crying in delirium, "He is no longer here, no longer here. How dark it is!" Gwynplaine came to her side, and Dea laid her hand on his head. "Gwynplaine!" she cried. And Gwynplaine received her in his arms. "Yes, it is I, Gwynplaine. I am here. I hold you in my arms. Dea, we live. All our troubles are over. Nothing can separate us now. We will renew our old happy life. We are going to Holland. We will marry. There is nothing to fear." "I don't understand it in the least," said Ursus. "I, who saw him carried to the grave. I am as great a fool as if I were in love myself. But, Gwynplaine, be careful with her." The vessel started. They passed Chatham and the mouth of the Medway, and approached the sea. Suddenly Dea got up. "Something's the matter with me," she said. "What is wrong? You have brought life to me, my Gwynplaine, life and joy. And yet I feel as if my soul could not be contained in my body." She flushed, then became very pale, and fell. They lifted her up, and Dea laid her head on Gwynplaine's shoulder. Then, with a sigh of inexpressible sadness, she said, "I know what this is. I am dying." Her voice grew weaker and weaker. "An hour ago I wanted to die. Now I want to live. How happy we have been! You will remember the old Green Box, won't you, and poor blind Dea? I love you all, my father Ursus, and my brother Homo, very dearly. You are all so good. I do not understand what has happened these last two days, but now I am dying. Everything is fading away. Gwynplaine, you will think of me, won't you? Come to me as soon as you can. Do not leave me alone long. Oh! I cannot breathe! My beloved!" Gwynplaine pressed his mouth to her beautiful icy hands. For a moment it seemed as if she had ceased to breathe. Then her voice rang out clearly. "Light!" she cried. "I can see!" With that Dea fell back stiff and motionless on the mattress. "Dead!" said Ursus. And the poor old philosopher, crushed by his despair, bowed his head, and buried his face in the folds of the gown which covered Dea's feet. He lay there unconscious. Gwynplaine started up, stretched his hands on high, and said, "I come." He strode across the deck, towards the side of the vessel, as if beckoned by a vision. A smile came upon his face, such as Dea had just worn. One step more. "I am coming, Dea; I am coming," he said. There was no bulwark, the abyss of waters was before him; he strode into it, and fell. The night was dark and heavy, the water deep. He disappeared calmly and silently. None saw nor heard him. The ship sailed on, and the river flowed out to the sea. |